a major Frederick Douglass manuscript discovery: recruiting the men of the 54th Massachusetts

DOUGLASS, FREDERICK. Autograph Manuscript Signed, comprising his list of men recruited for the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment and an account of his travels and the resulting expenses in that effort.

Various places, March-August 1863

12mo. 12 manuscript pages in a 40-page ruled pocket notebook. Original sheep inscribed on upper cover, possibly in Douglass’s hand, “F. Douglass’s—/ Account with G.[eorge] L.[uther] S.[tearns] / 54th Regiment Mass.” Rubbed, some staining, signs of handling and use.

This newly discovered manuscript documents the realization of Frederick Douglass’s dream that Black soldiers would fight for the cause of freedom in the Civil War. In this manuscript Douglass recruits African-American men to serve in the newly organized 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. One of the first Black units in the Army, the 54th Massachusetts quickly became the most celebrated Black regiment of the war.

The Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863 opened the way for Black men to fight for the Union cause. Frederick Douglass, who called the Proclamation “the greatest event of the century,” helped lead the effort to mobilize African-Americans to fight in the war. He wrote, “A war undertaken and brazenly carried on for the perpetual enslavement of colored men calls logically and loudly for colored men to help suppress it.” To Douglass, fighting in the war would help cement the claim of Black Americans to full citizenship. In March Douglass launched an extensive tour of New York, delivering his “Men of Color, to Arms, to Arms!” speech and enlisting recruits for the now-celebrated 54th Massachusetts Infantry.

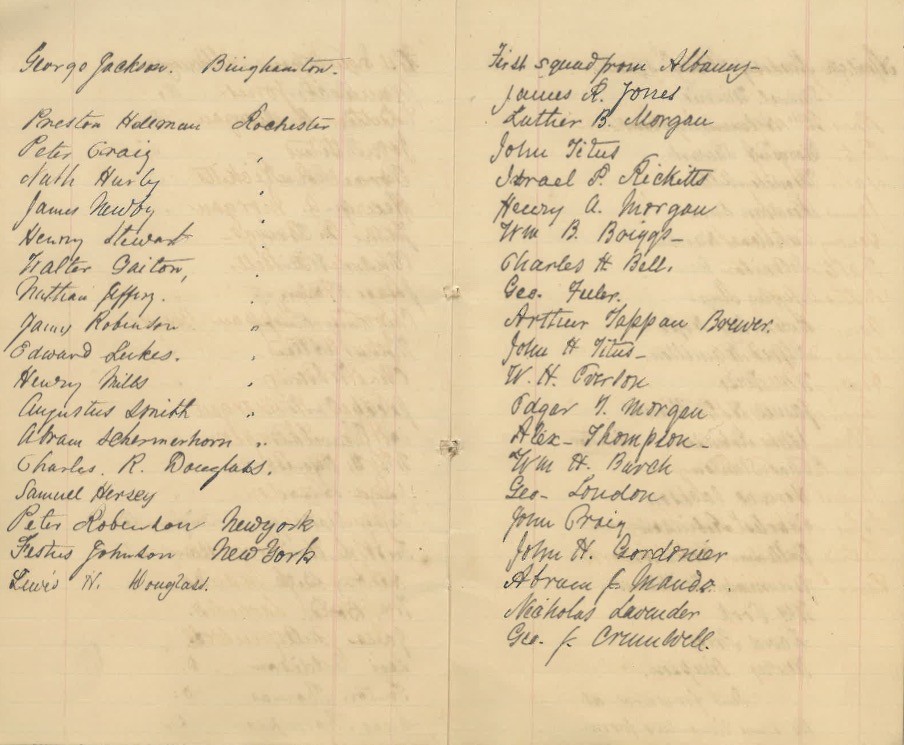

This previously unknown manuscript documents that recruiting drive. The first six pages cover March and April, when the recruits for the 54th Mass. were being enlisted. Douglass records his recruiting trips, associated travel and communication expenses, and the transport, lodging, medical, and food expenses for enlistees. Fellow abolitionist George Luther Stearns, who had backed John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859, paid the considerable expenses of this recruitment effort. These accounts also note the cash Douglass received from Stearns and from Gerrit Smith, another of Brown’s backers. An entry signed by Stearns commemorates a face to face meeting: “Buffalo April 13/63 / Settled to date / George L. Stearns.” The seventh page records Douglas’s expenses incurred in Pennsylvania and Ohio from late June to early August.

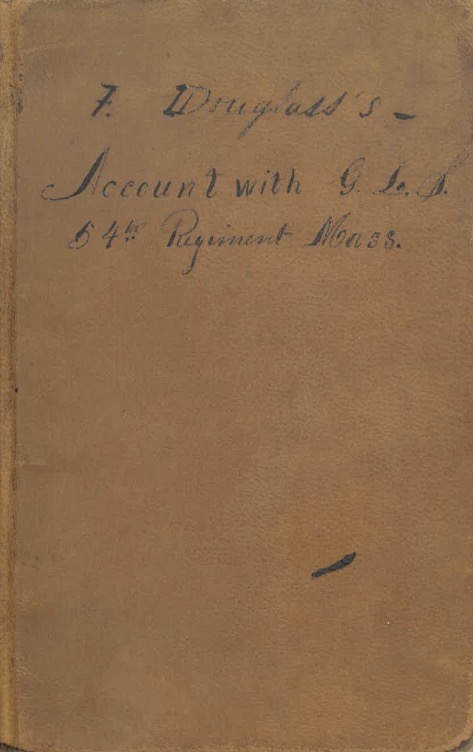

The final six pages list the names of the men Douglass recruited (including those of his own sons Charles and Lewis) as well as the names of their hometowns (New York City, Albany, Rochester, Syracuse, Binghamton, and Elmira). Most of the manuscript is in Douglass’s hand; a few of the later entries may be in another hand. In the end, Douglass personally recruited more than 100 men, as shown in this manuscript.

On May 28, 1863, cheered by great crowds, the regiment’s 1007 Black soldiers and 37 white officers marched through the streets of Boston on their way to war. The regiment’s heroism in the famous assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863 dispelled any doubts whites—of the North or the South—had about the valor, commitment, and skill of Black soldiers. The 54th Massachusetts numbered 600 men at the time of the assault. Of these, 272 were killed, wounded, or captured during the engagement. Frederick Douglass’s son Sergeant Major Lewis Douglass was among those wounded. He wrote to his future wife, “How I got out of that fight alive I cannot tell, but I am here. … Remember if I die I die in a good cause. I wish we had a hundred thousand colored troops we would put an end to this war.” The story of the 54th Massachusetts has been told in countless books, poems, works of art, and the 1989 film Glory.

This remarkable manuscript represents a defining moment in the life and work of Frederick Douglass. Here he achieves his long-held goal of seizing full citizenship for African Americans by fighting for their own freedom to end the war and slavery. To this great cause he offered his own sons Lewis and Charles, whose names appear in the manuscript’s roster of recruits.

Significant Frederick Douglass manuscripts are of the greatest rarity in the market.

Provenance:

1. Frederick Douglass.

2 Edward Gilbert, New York attorney and abolitionist, Vice President of the New York State Anti-Slavery Society, with his name and address written on first page in pencil. This may be an ownership marking or it may be a note made by or for Douglass. Gilbert was active in the Black recruitment effort. On July 31, 1863, the New York Times published a letter to him from War Department solicitor William Whiting promising that African-American soldiers would be given the same pay as whites, a major point of contention among African-American recruits.

3. Frederick Douglass Memorial Association, with its partly removed bookplate on front pastedown.

The survival of this manuscript has been unknown until now. Neither the Douglass Papers at the Library of Congress nor the Calendar of the Writings of Frederick Douglass in the Frederick Douglass Memorial Home, Anacostia, D.C. (1940) shows any trace of this manuscript. Likewise the papers of the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division reveal no reference to the manuscript. The Douglass Papers Provenance, Publication History, and Scope and Contents essay on the LC website states, “In 1945, as a safeguard against their accidental destruction or future dispersal, the Library of Congress filmed the Douglass papers then at the home. Since that time, some items have become separated from the collection.” The Douglass Papers were transferred to the National Park Service in 1962 and then to the Library of Congress in 1972.

$350,000